Seasons Greetings

Ads Worth Spreading

Side Project: Chicagoans for Rio

Chicagoans for Rio: The Pecha Kucha Presentation from fifteen ideas on Vimeo.

Jim Haven Wants to See Your Print Work

On the heels of the last two posts, here's something from Creature co-founder, Jim Haven.

On the heels of the last two posts, here's something from Creature co-founder, Jim Haven. R/GA on the Future of Agencies

Barry Wacksman & Nick Law of R/GA

12 Ways Digital is Different Than Traditional

Not exactly.

In some ways we’re the same. We’re briefed. We concept. We revise. We present. Hopefully, we sell. But behind closed agency doors there are a lot of differences between what digital and traditional creatives do. And while I have a writer’s perspective, all this stuff applies to you, too, art directors. Don’t reach for your Wacom tablets just yet. Now where to begin…

Digital creatives don’t make ads. That’s what traditional creatives do. TV spots, print ads, billboards, all that good stuff. Digital creatives develop experiences. Anything that involves a click and a call to action is more than an ad. It’s content. Sites, mobile apps, social media. Videos, products, services. These are all experiences that interact with people differently than traditional ads, both intellectually and physically. Even a static banner that drives to a website is an experience. Unfortunately, that’s why so many banners are ineffective – confused creatives think they’re making an ad.

Digital has to work harder. TV ads have no competition for your attention. They pop into your living room. Then they’re gone. But digital work will only be effective if people choose to spend time with it. It needs to be entertaining, provide utility or both. It takes much more strategic thinking to create a successful digital campaign. You can’t just throw ideas against the wall until one sticks. You’ve got to have a damn good reason for throwing an idea at that specific wall, at that certain time, at that very spot.

Digital doesn’t just talk. It starts a conversation. Digital isn’t about getting people to think something; it’s about getting people to do something. Click here. Proceed to check out. View this video. Take an action, any action, whatever it may be. Traditional media passively connects with people. It interrupts TV shows or appears in between magazine articles. Look at all the TV ads that drive to a brand’s site. Digital is where brands can really interact with people. Take AKQA’s recent award-winning Fiat Eco:Drive work. It’s not targeted at people buying cars, exactly. It’s aimed at people who are trying to decrease their carbon footprint. Fiat listened to them. Now they want to hear more from Fiat.

Digital knows how to multitask. The best traditional advertising does one thing. Spreads awareness, makes something cool, provides entertainment, gives a brand a voice. It falters when it tries to do too many things at once, or tries to reach too large an audience. But digital work has to do everything at once. It has to be functional and entertaining, clear and thorough, concise and explanatory. You don’t know who is viewing your work. Copy has to appeal to different users. A site isn’t going to talk to a first-time visitor and a diehard fan the same way. That would alienate both groups of people. If someone doesn’t like the experience you’ve created, they’ll go surf somewhere else.

The creative departments aren’t built with the same pieces. Traditional agencies are a 50/50 split of art directors and copywriters who usually work in teams. That’s not the case at digital agencies with design- and tech-heavy projects. (I’m not just talking about visual design. There’s user experience design, too.) Digital creative departments are a mix of copywriters, art directors, visual designers, user experience designers, and creative developers. That means writers work on more projects. Art directors become better designers. And everyone thinks more strategically.

Digital creatives aren’t paired with a partner. That’s not exactly true. We’re actually paired with partners all the time. A new one every project. In digital-based shops, it doesn’t make sense to permanently pair a copywriter with an art director. Depending on what the client wants, I could team with anyone from the creative department. What creative really wants to be monogamous, anyway? It’s not natural. Especially for people who choose to get into advertising.

There’s been a shift in the balance of workload. Digital work comes in all shapes and sizes. There are copy-heavy projects and design-heavy ones. Tech-based projects and strategic ones. I’ve written copy on my own, like when I authored seven articles for a client’s microsite. Then there are projects, such as visual branding assignments or web guidelines, that doesn’t require much input from a writer at all. That doesn’t mean anyone gets off easy. Everyone is still on the same team. Sometimes I work late watching the designers work their magic. Maybe they’ll need copy, maybe not. My doctor thinks I could use more Vitamin D, but I’ve made way cooler websites than him.

Digital art directors do more than think. We all know one. Those art directors who can’t draw and fumble through Photoshop. Who knows, maybe they get by on their “ideas.” Well, they’d never make it in digital. Just being able to come up with an idea doesn’t cut it. Digital art directors need to be able to execute and nail the minor details. They can’t rely on storyboard artists, graphic designers and post shops to do the dirty work. They need more talents in their toolbox. Which makes complete sense. If you love design, you should know how to do it.

Digital isn’t linear. Traditional ads live in a bubble. They have a clear beginning and end. Once a commercial has been shot and edited, it is what it is. But anything developed for the web evolves. Before coming to AKQA, I’d never created a 40-page copy deck. But that’s what happens when a project has copy for a brand site, a Facebook page, online banners, digital promotions, and mobile apps. Not to mention all the other shapes that pixels can take.

In digital, measurability isn’t a grey area. It’s black and white. Traditional has the luxury of being cool, philosophical or humorous because it’s building brand equity and setting the long-term tone. But there’s not a single brand in the world that would rather be loved than sell their product. Effectiveness is something that has to be taken into consideration for every digital project. Before a digital campaign launches, benchmarks are set. It’s clear whether any given campaign is a success or a failure. So while traditional creatives may say their project is cool, digital creatives can say their project was effective. And only one of those things is not subjective.

Digital happens faster. It takes a while for a traditional campaign to go from brief to launch. Factors like a shooting schedule and media buy can really bloat a schedule. But a digital agency acts as a creative agency and a production shop under one roof. Producing a project can be much more efficient. With the tech team across the room, we can see progress as it happens, instead of relying on outside vendors. That means less waiting around before an idea goes live.

The dinosaurs are going extinct. Being outdated and reactionary isn’t a problem for every traditional agency. Some of them are doing fine. But a lot of them aren’t. Some of them have become the places where creatives go to die. (Maybe not die - that’s a little harsh - but wrap up a career in peace.) As a young creative, the last thing you want is to be influenced by jaded industry vets who have already checked out. Digital doesn’t have the dinosaur problem. The whole industry is too new. It draws the best talent. The most eager talent. It’s not just people into advertising. It’s people into the latest trends and technology. I chose AKQA because of the people. More smart, dedicated people under the same roof than I’d ever seen before. It was something I wanted to be a part of.

If you’re breaking into advertising, you have a choice to make. Traditional vs. digital. David vs. Goliath. The blue pill vs. the red one. There’s no doubt traditional agencies are learning from digital ones, trying to avoid extinction. While digital agencies are busier than ever and getting more traditional assignments. Then there are these so-called integrated agencies popping up left and right, at least on letterhead. True integration is easier in theory than practice. The most important thing is to find a place where you can do the work you want to do. And then kill it.

If you’re breaking into advertising, you have a choice to make. Traditional vs. digital. David vs. Goliath. The blue pill vs. the red one. There’s no doubt traditional agencies are learning from digital ones, trying to avoid extinction. While digital agencies are busier than ever and getting more traditional assignments. Then there are these so-called integrated agencies popping up left and right, at least on letterhead. True integration is easier in theory than practice. The most important thing is to find a place where you can do the work you want to do. And then kill it.Notice anything else? Leave a comment.

The Kind of Creatives We Need to Be

If you're a Chick Corea fan, you know he's one of the most amazing jazz pianists ever. Who knew he played the drums? But it makes perfect sense. He's not just a pianist. He's a musician.

Look at how effortlessly he picks up the sticks and starts playing. Meanwhile, his bass player sits down at the piano and starts jamming just as easily.

That's the kind of creatives we need to be. Art directors need to be able to write. Writers need to be able to art direct. UX guys need to be able to understand media. We all have our specialties. But need to be more than specialists.

Otherwise, we're just the drummers who throw in a little extra cowbell.

The Mentor Effect in TalentZoo.com

A Slightly Better Video Than Mine

Getting Better: A Christmas Story

Read this at 11:15 pm, right before you leave the office.

That’s how it works on paper, anyway.

But here’s an argument that’s also worth considering: In advertising we pride ourselves on the ability to draw from our own experiences to create really insightful, moving advertising. But by spending more of our time in the office under halogen lamps, the fewer real experiences we’re going to have, and the more our work may suffer.

Again, that’s theory. But it’s an argument we don’t really allow ourselves to hear in this industry.

But beware of places where the culture is “work until nine, or you’re slacking.” Don’t avoid them. But beware of them. And no matter where you end up, when you start burning the midnight oil, ask yourselves if it’s really to make your ads better, or because you want the people in the cubes next to you to think you’re a hard worker.

Great creative is a badge of honor. But staying late shouldn't be.

Radio On! Creative Workshop

The Future of Advertising Article in Fast Company

A friend of mine sent me a link to a really good article in Fast Company today about the future of the ad biz wanting to get my take on it. You should check out the article. It's long, but it's packed with knowledge.

As a somewhat lazy blog post, here's what I wrote back to my friend:

I read this, and I think a little bit of it is overly dramatic and alarmist (any article called "The Future of Advertising" is bound to be). I also see some executives freaking out because they haven't been paying attention to/believing in what's been happening for the last 5 years. But I also think there's a lot of truth in this, a lot of really smart people trying to figure out what the hell to do. Things are not necessarily broken with the type of thinking we do, it's more in the structure of the agencies and the billings and what the relationships look like.

I think you and I both know that a good idea is a good idea. Execution, all that stuff comes into play. But a smart creative should be able to come up with ideas in whatever format. All that said, for our own careers, we need to be able to look at the agencies out there and assess which ones are figuring it out and which ones are going the way of the Triceratops.

Here are some of the themes I see for the future agency:

SMALLER. Trim the fat salaries. Trim the layers. Trim the holding companies. It's the pods theory. Small, independent teams of 4-7 smart people.

CREATE VALUE. It's not about what we're saying. What are we giving people?

NIMBLE. Adapt and respond quickly.

RESOURCEFUL. Get it done without the waste. You have a battery, a toothpick, a plastic baggie and some table salt to work with. Make a hydrogen bomb.

VERSATILE. Work in any medium, create content, buy media, be connected.

A lot of questions about the big monoliths, and a lot of visionary people who could easily coast off into the sunset are starting to grab their parachutes and jump. To me, that's the biggest signal that these changes are real.

What do you think?

The Fallacy of the Fried Mermaid

I'm reading Improv Wisdom: Don't Prepare, Just Show Up by Patricia Ryan Madson, and I just finished a chapter in which she explains what she calls "The Fallacy of the Fried Mermaid."

At an improv show, the performers will sometimes ask the audience for a suggestion: "Give us a _______ in a ________" in which to build a scene (e.g. "a chicken in a bowling alley"). Without fail, the audience will try to think of something wacky or weird. There is the perception that this is more creative and will lead to a better scene.

That is the "Fallacy of the Fried Mermaid." A fried mermaid is already a joke. There's no punchline left. As Madson says, "It's a closed loop...Doing an actual scene about a fried mermaid isn't likely to result in a very appealing story, if you think about it."

Weird for weird's sake, is what I usually call it. When discussing a comedy spot with directors, I almost always say "I don't think this should telegraph funny," or "The casting shouldn't look funny." Humor is based on surprise, and making something look funny is the equivalent of starting off a joke with "Oh, I have this hilarious joke to tell you."

Madson continues:

Don't fall for the idea that something needs to be "way out" or whimsical to be creative. Getting a laugh is easy--trivial, actually. Anything unexpected seems funny. This kind of humor is like a sugar hit. It gives temporary lift, but it is like a poor diet and won't nourish artistically. If you give up making jokes and concentrate on making sense, the result is often genuinely mirthful. Besides, making sense is a lot more satisfying in the long run. Give the obvious a try.Incredibly applicable to what we do.

As a counter examples to this, I could use one of my favorite spots:

That said, I think the weirdness of the casting, etc., is about establishing the world in which the spot takes place and is integral to the idea. Weird is not the idea in itself.

Radio Lessons from Ira and Alec

This Post Isn't Cool

How to Read CA

When you get your copy, try this:

When you get your copy, try this:"Constantly Being Out There"

I was in portfolio school the first time I heard about Fairey. It fact, I don’t even think I heard about him. What I heard was, “There’s this guy who makes these Andre the Giant stickers and gives them away for free. They’re pretty cool. Look, there’s one on the back of that stop sign over there.”

Years later, he’s the guy who designed the first presidential portrait to be purchased by the United States National Portrait Gallery before the President had been sworn into office.

What this former schoolmate of Fairey's told me was this: “I honestly don’t know if ‘Andre the Giant has a Posse’ is a great concept or not. It could be brilliant. It could be absurd. Maybe both, I don’t know. What I do know is that never quitting, and constantly being out there can make all the difference.”

Carl Sandburg and Manifestos

We've written before about manifestos. A well-written one can be a powerful opening to a meeting. Couple it with the right art direction, and a great manifesto can sell a campaign, even if it never appears as a print ad or in the voiceover.

We've written before about manifestos. A well-written one can be a powerful opening to a meeting. Couple it with the right art direction, and a great manifesto can sell a campaign, even if it never appears as a print ad or in the voiceover.The silent litany of the workmen goes on –

Speed, speed, we are the makers of speed.

We make the flying, crying motors,

Clutches, brakes, and axles,

Gears, ignitions, accelerators,

Spokes and springs and shock absorbers.

The silent litany of the workmen goes on –

Speed, speed, we are the makers of speed;

Axles, clutches, levers, shovels,

We make signals and lay the way –

Speed, speed.

The trees come down to our tools,

We carve the wood to the wanted shape.

The whining propeller's song in the sky,

The steady drone of the overland truck,

Comes from our hands; us; the makers of speed.

Speed; the turbines crossing the Big Pond,

Every nut and bolt, every bar and screw,

Every fitted and whirring shaft,

They came from us, the makers,

Us, who know how,

Us, the high designers and the automatic feeders,

Us, with heads,

Us, with hands,

Us on the long haul, the short flight,

We are the makers; lay the blame on us –

The makers of speed.

(I'm not expecting any takers on this, but if any of you art directors want to art direct Sandburg's poem and submit it, we'll post it, tweet it, link to your portfolio and sing your praises.)

Pre-Roll Is Broccoli

I was at the Oakland Airport the other day and was pumped to see that they now have free wi-fi. That is, free wi-fi for 45 minutes, if you sit through a commercial. Awesome, right? Free wi-fi? And all I had to do is sit through a 30-second commercial?

Then a couple days later, I was watching a video online, for free, and there was a discreet "Brought to you by MINI" up above the video player. No pre-roll.

So here's my question: Which of these models is better for the brand?

Traditional thinking would say that the one where you get the full brand message (i.e. option A) is the better. The brand spent all this time crafting a strategy and money producing a commercial--they want people to watch it.

But the problem with this is that it positions the advertising as something negative. It's the work you have to do before you can enjoy the reward. It's the broccoli before the ice cream sundae. The barrier between you and what you want. The negative end of the trade-off. The cost. In short, not where we want our brands to be.

Option B, the little logo, represents more modern thinking about a brand's relationship with its consumers. What is Mini giving me? An interruption-free video? Awesome! Thanks, Mini! In this case, the brand is the bowl in which the ice cream sundae is served. I like that bowl, and I'm left feeling good about the brand. It has given me something I want. Sure, I didn't get a "message," but I have a FEELING (I would argue that's more important anyway).

We're at a pretty pivotal time in the way advertising is perceived. The old model sets up advertising as annoyance. It interrupts our shows. Delays our movies. Clutters our scenery. Do we really want to carry this legacy forward online?

This is a media question. In the traditional model, it was answered by the media folks. A lot of agencies and media companies still work like this. It's all about the numbers--the GRPs and Impressions and Clicks. But media has become the responsibility of everyone. If you're a creative, it's a conversation you should be involved in, because it influences how people view your creative and your brands. So get in there and ask questions, start conversations and, most important, be thinking of alternative solutions.

Yet Another Agency Video

Your Book vs. Your Agency

Here's an interesting quote from Andrew in Creativity:

Here's an interesting quote from Andrew in Creativity:The latest batch of inspiration

Complaining

Ads as Art?

I recently finished the book Adland, by former copywriter and creative director James Othmer. In it, he actually asks Fenske this very question. Is advertising art? He gets a gruff snort from Fenske. Then, after some consideration, Othmer gives what I think is the most insightful answer to the question I've ever heard:

"It doesn't matter whether I think advertising is art. What matters is whether its creator does."

There Goes The Neighborhood

Compared to Firstborn's, what do you think?

More On Branding An Agency

Anyone who watches Mad Men saw Don Draper issue a similar statement this season when he took out a letter stating that Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce would not work for cigarette accounts. Setting aside the moral dubiousness of being the Lucky Strike agency one moment, then taking a moral stand the next, Don essentially put a stake in the ground and said, “this is the kind of agency we are. Take it or leave it.” (Apparently, Jay Chiat, among others, ran similar ads on tobacco back in the day.)

As Greg has pointed out, “Look at the ABOUT US section on most agency sites and it will say, ‘We are a full-service marketing communications agency, specializing in broadcast advertising, digital media, corporate branding and public relations.’” The same is true of most agency videos. They’ll talk about changing media (duh), the need to make lasting, meaningful relationships with consumers (no kidding), and that social media has shifted conversations blah blah blah blah. We rarely do a good job of distinguishing our own agencies from all the others out there (ironic, since building memorable brands is our job).

Here’s a video from Firstborn that says pretty much everything most agency websites say (client roster, quick portfolio of work, importance of technology, a sense of the agency’s culture).

It conveys all of this without the use of a narrator or flashy titles. I think it does a pretty good job. At the very least, it makes me feel something about the agency (isn’t that what we try to do with most of our work—get someone to feel something?).

What do you think?

On Sloppiness

So make mistakes. Just don’t be sloppy.

"You will be fierce. You will be warriors."

Stop Being Such a Baby

Maybe it’s wanting to shed a label you think no longer applies. Maybe it’s wanting more of the creative opportunities that usually go to the senior creatives. Maybe it’s just about ego. Whatever the reason, getting people to see you as something more than a junior creative can be harder than it should be.

Here are a few ways you can stop being a junior. With two caveats:

- This has nothing to do with politics, brown-nosing, or acting like someone you’re not. That stuff will get you nowhere.

- Reasons for advancing vary from agency to agency. The size of the shop and your relationship to the people in it have a lot to do with it.

Work hard.

Duh. If you produce great work, it will be recognized. By your bosses. Your peers. Headhunters and other agencies. Just make sure you don’t confuse working hard with treading water.

Stay at the same place for a long time.

Some places may promote you eventually. This requires patience and the afore mentioned “hard work.” But when you’re not only invested in the company’s culture, but you’ve helped maintain and build it, you should be bumped up eventually.

Ask for a promotion.

Tell your CDs that you want to advance. That you want to spearhead a pitch. Or have more facetime with the client. Don’t expect it to happen immediately. But let them know where you see yourself in five years. Then do what it takes to put yourself there.

Be lucky.

You have so little control over this, it’s almost not worth mentioning. But there it is.

Get another job.

This is probably the most effective way for junior creatives to become non-junior creatives. New agency. New faces. Suddenly no one knows you as a junior. It's also probably the most effective way to increase your salary. Just remember, the better your work, the better chance you have of getting the job and opportunities you want. It always comes back to the work.

One Way to Get a Job

Not a bad idea if you're shopping around in one city. I'd be interested to know what these guys will do if they get an interview in London or somewhere outside of Stockholm.

Not a bad idea if you're shopping around in one city. I'd be interested to know what these guys will do if they get an interview in London or somewhere outside of Stockholm.Radio Word Counts

The Radio Mercuries are here! The Radio Mercuries are here!

Say My Name, Bitch

The etymology of branding starts with cattle. In order to tell one rancher's cows from the thousands of other virtually identical cows on the range, ranchers would brand them with a unique mark. Theoretically, the branding we speak of when we gather in agency and client conference rooms across the globe is a little more sophisticated. Branding shouldn't be synonymous with "labeling." It should be more like "brand character development." I should be learning something about your brand or product. You should be giving me something, adding something to my life, creating a positive association with your brand. Something to help me like it.

Yet, in any creative presentation, we hear: "I'd like to see more branding." "More branding upfront." "More brand registration." In other words, say our name, show our logo, and then say our name some more. Because, as we all know, someone repeating their name over and over and over makes us like them. "Hi, I'm Billy. It's my name. Billy. Billy is here!"

A lot of brands put their ads through quantitative testing. Companies like Ipsos ASI have perfected the art of making billions of dollars by dumbing down creative work, mostly by insisting that they need "more branding." They do this because they believe in an inherent link between engagement, recall and likability. In other words, people remember what they like. Which seems true. But it also leads to the foolish belief that I can make you like my brand simply by repeating my name enough. Being memorable is not the same as being likable. If I burn my name into your arm with a hot metal poker, I can guarantee you'll remember me. Does that mean you'll like me?

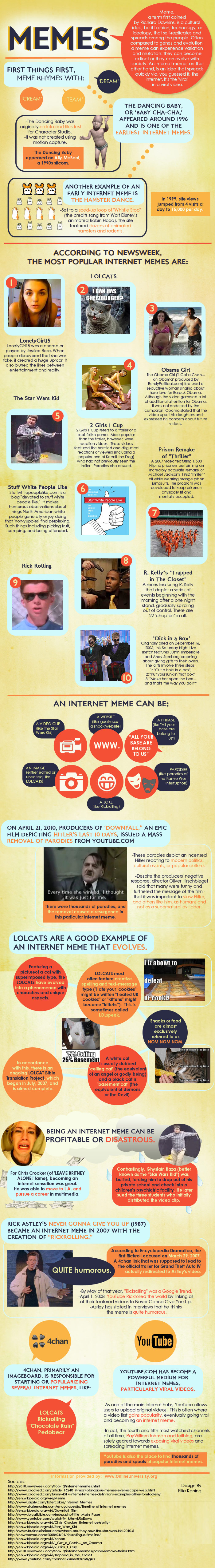

In the latest example of this confused philosophy, a company called Solve Media has developed a system by which CAPTCHAs are branded. You know CAPTCHAs. They're those squiggly words you have to decipher when you buy tickets online, etc. They basically verify that you're a human.

I think most of us would agree that CAPTCHAs are fairly annoying. A necessary evil at best (however, as an aside, I do find the use of ReCAPTCHAs to be a cool, innovative solution to two problems at once). So the brainstorm of the people at Solve Media is to create branded CAPTCHAs. Instead of typing in "contribute of," you might be asked to type in "The Ultimate Driving Machine" or "Just Do It" (though I doubt either BMW or Nike will engage in this type of "branding.")

Here's a little video championing this innovation:

Solve Media from Solve Media on Vimeo.

The problem here is twofold:

1) You're associating a brand with something annoying and intrusive. What are you giving me here? You're standing between me and something I want with your stupid slogan. Rather than walking away with a positive impression, I'm irritated, and your brand is the source of my irritation.

2) This is amoeba-level marketing. Just because I see your slogan doesn't mean I like your brand. "Hi. It's me again. Billy. Remember me? I told you my name earlier. It's Billy! Billy is here!"

Come on, folks. We can do better than cattle branding.

Google Scribe a Celebrity

Here's one that taps into a new offer from Google Labs.

Modernista Is Not For Everyone

If you go to Modernista's Website, you find a unique and inspiring message. "Modernista is not for everyone."

Many agencies will take a shot at any client they think they can win. But an agency with a good sense of who they are and who they want to be realizes that they can't be the right agency for every client. Like a brand, they have a character. Taking on the wrong clients will dilute that character pretty quickly.

Understanding what your agency's brand is can be just as important as understanding your clients' brands. But, as Tim Williams points out in Take A Stand For Your Brand, agencies can be surprisingly bad at defining and understanding their own brand. We tell our clients they can't be everything to everyone. We would be wise to heed our own advice.

Madison Ave vs. Silicon Valley

Cover Letters

When you start sending out your portfolios, you’ll want to include a cover letter. That said, I don’t think many creative directors make time to read cover letters. So I’m offering the advice I got in portfolio school, which I’ve used ever since:

1. Tell them why you like their agency.

2. Tell them the job you want.

3. Tell them why you think you'd be a good fit.

4. Give them your URL, PDF or however you're showing your work.

5. Tell them you'll follow up with a phone call in the next couple of weeks.

Pretty simple. And I’d shoot for a word count of under 120. (Exactly the number of words that are used in this post.)

The New Yorker, iPhones, and Experimentation

Collaboration

Character > Message

I was asked to do a guest editorial for the local ad blog, the SF Egoist. It's about how we tend to neglect brand character for the sake of message, and what we can learn about character development from fiction writers. If you're interested, you can check it out here.

My Ad Anthem

The Mentor Effect

SxSW Favor

Running Short

The coach (who’d been a 400 meter state champ himself) knew that after conditioning this kid’s mind to run for 800 meters, running the 400 in the qualifying tournament would seem like a piece of cake.

Turns out it worked. The kid went on to win the state championship, and break his own coach’s state record.

Here’s how this applies to you writers and your radio scripts: Start writing 30-second radio scripts instead of 60s.

It’s tough to get a script to fit into 60 seconds. But squeezing a great idea into 30? That’s almost torture.

Sure, 60’s are standard. But I’m seeing a lot of clients who are buying 30s – especially in this economy. Some clients buy them because they’re less expensive. Some buy them based on media buyer’s recommendations. And some buy them because they don’t believe in or care about radio.

But that doesn’t mean you can’t do great 30 second radio. Just visit the Radio Mercury Awards site and hear what I mean.

:30s and :60s are different beasts. What works in one might not work in the other. But practice writing a few. Because if you can write a fantastic :30, you’re going to be that much better at writing :60s. Not to mention TV spots, headlines, and concepting in general.

Know When To Work

You should figure out what works best for you. If you work best at night when it's quiet, try to get in the habit of sitting down and at least jotting down some ideas then. And if you feel like you're in the mood, don't let it pass you by.

A few months ago, Greg posted the idea from Stephen Covey that our tasks can be divided up by their urgency and their importance. He basically argued that we spend most of our time doing urgent but unimportant tasks, leaving important things with no deadline (all those big ideas that you'll get to one day) on the back burner permanently.

My good buddy Brian Button just sent me this great post from Mark McGuinness that argues essentially the same thing. To him, we get our priorities backwards, doing reactive work (emails, returning calls, etc.) first and leaving our big creative tasks for the dusty hours of the day, when our brains are running on fumes. Thus, our novels never get finished, our websites remain half-vacant and our great side projects never become more than cryptic sticky notes above our desks. I encourage you to read Mark's post. Creative people are fueled by the big ideas. We do ourselves a disservice when we don't follow through with them.

When a Great Visual Isn't A Visual

Unless you've been living in a cave, you've heard of Steven Slater--the now-famous Jet Blue flight attendant who recently quit his job by giving a verbal lashing to a passenger over the aircrafts's PA system. He then deployed the emergency slide, grabbed a beer from the bevvy cart, and slid to freedom (until he was arrested shortly thereafter).

I was listening to a podcast the other day, and someone said that one of the reasons this story has captured the imagination of people everywhere (other than the fact that 95% of us wish we had the nuts to deploy our own escape slides) is that the visual of it is so good. That struck me as spot on. I have not seen, nor been able to find, an actual image of Slater descending the big yellow inflatable slide, beer in hand, but ten years from now I'll remember that story as if I'd actually seen a movie of it.

I think my favorite visual description ever is in Jitterbug Perfume, by Tom Robbins. He describes two women walking up a stairway: "Their backsides swung like mandolins on a gypsy wagon wall." Such a simple set of words, yet I can picture it exactly. The shape of mandolins. The way they sway in approximate unison, bouncing slightly. The fact that this is a gypsy wagon adds a certain attitude to the way they move. It's what you might call theater of the mind.

When a radio spot is visual, you'll often hear people say that. Theater of the mind. The spot conjures a clear image in the mind of the listener. All radio should do this. But really, all writing should do this. Most people remember visually (ever hear of the memorization trick where you construct a house in your mind, then assign the things you need to memorize to parts of the house?--you're building a visual to help you remember). So anytime you can create a strong visual, you should.

But as we've seen, not all visuals are literally visual. And sometimes they're better that way.

The other day, a student was showing me the concept for an ad in which a young kid was standing over a pride of lions feasting on their kill in the middle of the Serengeti. I asked him to see what happened if he tried to tell the same story with a headline. I don't know if it'll be any better, but the thing I've found is that often, especially when an image is a little ridiculous, a headline is a better visual than a visual would be. That is, letting the audience imagine an image is often more powerful than just showing it.

Consider this ad from Carmichael Lynch for Motorola walkie talkies:

What are you seeing? The visual is some kids waving from a boat. But what we're all really seeing is poor Paps with his head jammed in the pump. I don't even know what a bilge pump looks like, but the image I have in my head is pretty damn funny. Much funnier than if they'd just shown Grandpa stuck in a pump.

When you let the audience imagine the scene, you're involving them. That's something you always want to do. Of course, to do it right, your language had better be spot on. Your words need to be tangible. They need to be specific. "Bilge pump" makes the Carmichael Lynch ad. And your words need to be accurate. Even though I have never seen mandolins swinging on a gypsy wagon wall, I know that I am seeing the exact same bottoms in my head that Tom Robbins saw in his head when he wrote that line.